How legal educators are getting it wrong

Don’t get me wrong. I love legal educators. Legal educators are my people. After leaving private practice, I spent 6 years teaching law and 10 years in continuing legal education and bar admission. I am a die-hard ACLEA-ite (and proud ACLEA Past President). Some of my favorite people in the world are law professors or continuing legal education providers. They do great work—and they are getting a lot right.

That said, in the spirit of lifelong learning and continuous improvement, I think it is important to acknowledge some of what we have been getting wrong.

How legal education misses the mark

We could talk about several aspects of legal education—including delivery methods, assessment processes, student experience—but this post is about something more fundamental: the content of legal education. In the last decade, I have reviewed hundreds of continuing legal education brochures from providers across North America. I am familiar with all bar admission programs in the country. I have reviewed websites and, where available, course outlines from countless law schools. Across them, I have found a thorough treatment of all major areas of legal knowledge and many important lawyering skills.

So, where are legal educators going wrong?

Professionals need more than discipline-specific technical competencies (such as legal knowledge or lawyering skills). They need an array of what we refer to as “professional foundations.” It is the lack of these professional foundations that continue to feed the evils that plague our profession today: attrition, addiction, burnout, inefficiency… Moreover, it is the lack of these professional foundations that threaten to rob lawyers of safe, effective, and successful futures tomorrow.

Lawyers are multidimensional beings

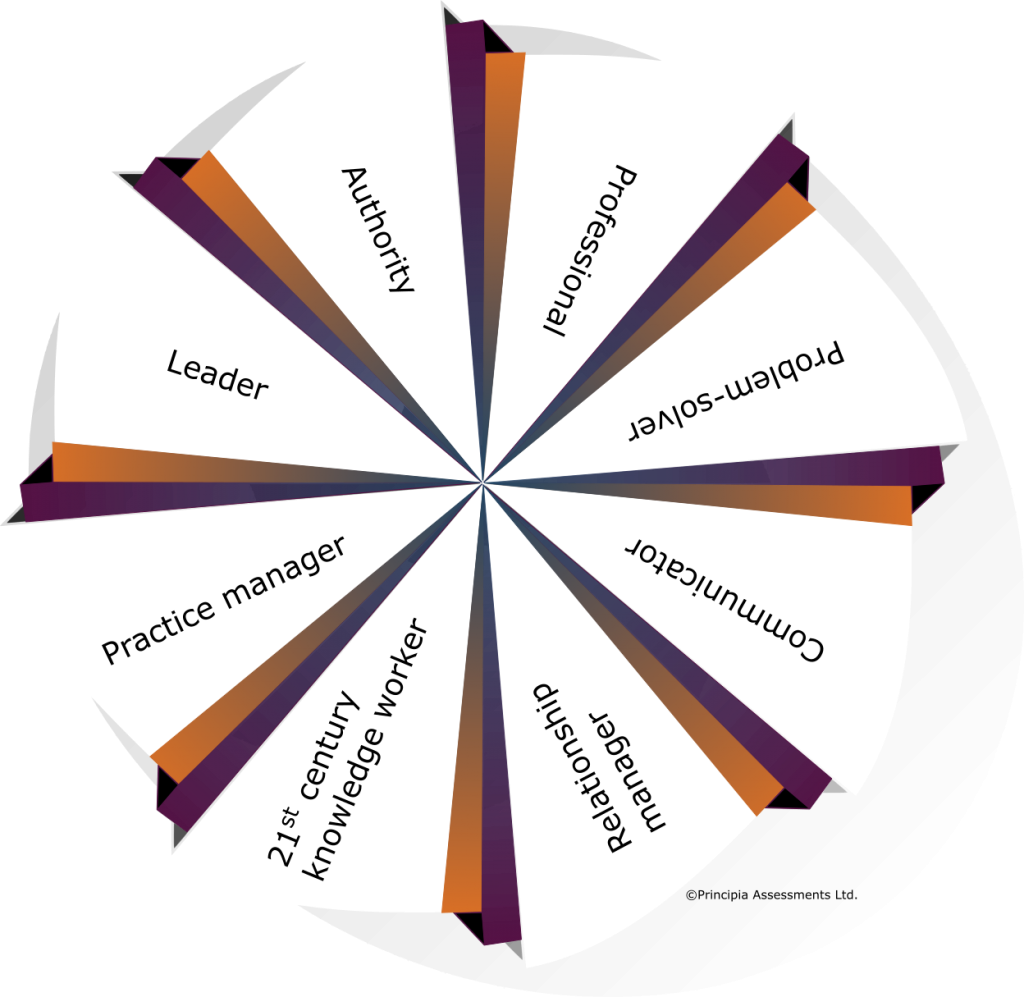

Lawyering is not a one-dimensional activity. To be effective practitioners, lawyers need to integrate a range of professional foundations with legal knowledge and specific lawyering skills. Lawyers, in their various roles, wear many hats. They are:

- Professionals. Lawyers are expected to demonstrate ethical and professional conduct that enhances the reputation of the profession. This includes making ethical decisions but also extends to exhibiting “practical” professionalism.

- Problem-solvers. Lawyers must solve problems and make decisions. They need a logical, integrated process for using their professional judgment.

- Communicators. Lawyers are called on to communicate effectively in a range of forms and contexts. They need to communicate orally and in writing; they need to adapt their communications for varied audiences.

- Relationship managers. Lawyers need to manage relationships with clients, colleagues, and others, working effectively with a range of individuals and teams.

- 21st century knowledge workers. Lawyers must plan, monitor, and manage their work effectively and efficiently, appropriately leveraging technology.

- Practice managers. Lawyers must sustainably manage the business aspects of their professional practices, including developing a strategy and plan, hiring and supervising others, and being financially responsible.

- Leaders. Lawyers must engage in lifelong learning, ideally striving for continuous improvement. They are expected to develop connections, serve their communities, and inspire others.

- Authorities. Lawyers need discipline-specific technical knowledge and skills in their chosen fields.

As the demands on the legal profession continue to evolve, the roles of “lawyer as… professional, communicator, relationship manager, 21st century knowledge worker, practice manager, and leader” become even more vital than “lawyer as technician.” Lawyers today—and more importantly, lawyers tomorrow—need the professional foundations that underly these roles.

More than discipline-specific technical competencies

That lawyers need more than discipline-specific technical competencies is not news. For example:

- National Entry to Practice Competency Profile. In 2012, the Council of the Federation of the Law Societies of Canada (FLSC) approved the National Entry to Practice Competency Profile for Lawyers and Quebec Notaries (NCP). The NCP was developed with assistance of law society leaders and staff, as well as practitioners from across Canada, under the guidance of a consultant specializing in credentialing. The NCP includes skills in communication, analysis, client relationship management, and practice management, in addition to legal knowledge and specific lawyering skills.

- Educating Tomorrow’s Lawyers Foundations for Practice. An initiative of the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, Educating Tomorrow’s Lawyers (ETL) devotes its work to aligning legal education with the needs of an evolving profession. The ETL Foundations for Practice project is a national, multi-year project designed to, among other things, identify the foundations entry-level lawyers need to launch successful careers in the legal profession. In total the foundations report identified 147 foundations; this included 40 lawyering skills, but also more than 40 characteristics and more than 60 professional competencies.

- Soft Skills for the Effective Lawyer. In Soft Skills for the Effective Lawyer, Randall Kiser (2017) describes and applies hundreds of multi-disciplinary studies in the areas of psychology, law, and “soft skills.” [Kiser, R. (2017). Soft skills for the effective lawyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.] This must-read book includes a summary of the most recent studies of essential lawyering skills. It confirms lawyers’ “soft skills” remain “woefully underdeveloped” (p. 35).

This recognition can also be seen in recent developments, such as:

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) calls to action (#27 and #28) to “ensure lawyers receive appropriate cultural competency training”; and

- The (U.S.) National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being that notes that “[t]o be a good lawyer, one has to be a healthy lawyer” but that “[s]adly, [the legal] profession is falling short when it comes to well-being” which raises “troubling implications for many lawyers’ basic competence.”

Despite this, virtually all law school courses and continuing legal education programs focus on substantive areas of law.

More than “kale in a smoothie”

“But Jen,” I can hear the voices already, “we cover these underlying professional foundations as PART of substantive law courses.” Even if you do, it isn’t enough.

It is a tactic, to be sure—and one I have used.

When I worked for a CLE provider, we frequently snuck various non-substantive-law topics into our substantive law programs. It reminded me very much of how I used to sneak kale into my kids’ smoothies. [Vegetables—like wellness, emotional intelligence, and cultural competence—are good for you.]

While there are some advantages to this approach, this doesn’t go nearly far enough. Competency profiles, course outlines, learning outcomes, and marketing materials all contribute to how professionals see themselves and what they recognize as important to safe, effective, and sustainable practice.

When nearly all law school courses and continuing legal education programs are called “Family Law 101” or “Criminal Law Update,” what message are we sending about what it takes to be a safe, effective, and successful lawyer?

Lawyers aren’t children. We need to serve them actual vegetables, not just kale hidden in a smoothie. They need to know that safe, effective, and sustainable practice is as much about managing relationships, being an effective 21st century knowledge worker, and communicating effectively as it is about being aware of the latest child support guidelines, changes to rules of civil procedure, and the latest supreme court jurisprudence. Having the latter is essential, but without the former, it isn’t enough.

On the right track*

I am watching with interest some of the developments we are seeing from law schools, such as the new proposed law degree program at Ryerson University (Ontario), the Calgary Curriculum, the Suffolk University Law School (Boston) Legal Innovation & Technology Certificate Program, and the Queen’s Law Graduate Diploma in Legal Services Management.

I believe these programs cover some important topics. More than that, however, I applaud that these law schools have named their courses for the competency areas they represent.

We are excited to watch for (and report on) how other legal educators will evolve to show their commitment to professional foundations.

Jennifer

*Updated on April 26, 2019 to reflect recent developments.